Make room! Make room! Harry Harrison’s seminal science fiction novel about overpopulation is (kinda) coming true. Except, it’s not an overpopulation of people that’s afflicting the planet, but an overpopulation of words. AI models are spewing out billions of words into the world. Does this mean that the value of the written word is set to spiral to zero? Let’s take a look…

Defining the written word

Before we begin, I’m going to define what I mean when I talk about the written word.

The written word is one that has been created by a person. A real, living, human being. They have engaged in cognition and then transmuted those thoughts into words; via a pen onto paper, or a keyboard onto an electronic document.

They haven’t generated or prompted words.

The point of this essay is to examine the value that - I believe - is inherent in taking the time to create and write words yourself.

The epistemological value of writing

If you read nothing else in this essay, then read this. This is the crux of my argument - writing has epistemological value.

What is epistemology?

Epistemology is the theory of knowledge. At the risk of vastly oversimplifying things, epistemology is essentially the study of how knowledge develops, determining what can and what cannot be known.

I like to summarise it as - the study of how knowledge develops within a society. How do people learn? How do people figure out what is possible to know? Through epistemology.

I appreciate that that may still be a little abstract, so let me boil it down further.

Writing is thinking.

The process of writing about a topic forces you to learn about it. The process of translating thoughts into words on a page imbues you with the knowledge that you may not heretofore have had.

If you outsource your writing, you outsource your thinking.

Writing is hard work. This is especially true if you’re writing anything beyond the mundane.

But, like anything that involves effort, it pays dividends. Those dividends? New knowledge and understanding of a topic.

Put in the context of a marketing and advertising agency like Velstar, writing plays an important role in developing a deep and acute understanding of a brand’s products and/or services.

The job of a copywriter or content writer (there is a difference between the two) in a creative agency is to act as the oracle that delves into a topic, wrestles with it, sweats over it, and becomes the ‘subject matter expert’ (to use a nauseatingly corporate phrase).

From there, that information (should) be transmitted to the other teams within the agency - providing succinct insights that can create better, more accurate, and more effective campaigns that truly communicate the USPs of a brand's service/products.

Outsource your writing to a large-language model and you’ve effectively outsourced the thinking, research and learning that creates truly effective marketing campaigns.

At this point, I appreciate this sounds like a pitch to keep my job (and, if the Silicon Valley tech bros had their way, it would/will be). But, I truly believe that - with about 15 years’ writing experience under my belt - there’s no better way for an advertising agency to create truly effective campaigns than to put the hard work in, sit down, and write about a topic.

The lessons of history

Don’t take me at my word.

Consider the role that copywriters traditionally played in advertising agencies.

If you’ve ever watched the TV series Mad Men, you’ll know what I mean.

Becoming a copywriter was a coveted position within the ad world. Don Draper - arguably the most important character within the fictional Sterling Cooper ad agency - was a copywriter.

He spent his days writing and thinking, thinking and writing, to create memorable, iconic, award-winning ad campaigns.

This isn’t merely a flight of fancy though. It’s borne out by such real-world greats as David Ogilvy.

There's a good reason he was known as the ‘Father of Advertising’.

Consider one of this most famous campaigns; the Rolls Royce ad.

I’m probably not going to be able to include a picture of the ad itself here due to rights issues, but its focal point is a quotation in large print:

“At 60 miles an hour, the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock”.

It’s a perfect encapsulation of what makes Rolls-Royce cars so special. At a time (1950s to 1960s) when the average car would be afflicted with road noise, engine noise and more, Ogilvy was able to summarise the uniqueness of the Rolls-Royce experience in a single sentence.

Incidentally, the campaign resulted in a 50% year-on-year increase in sales for the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud in 1958 following the release of the ad campaign.

But, how did he arrive at that stellar sentence?

Reading. In an interview after the fact, Ogilvy said that he spent three weeks reading about the car - particularly its technical manual.

The process of reading and writing, writing and reading about Rolls-Royce’s new product allowed him to create a campaign that bore significant success.

Now imagine if you outsourced all that work to AI. Well, there’s no need to. I asked ChatGPT 4 to: ‘write me an advertising headline to promote the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud’. Here’s what it produced:

Utter dreck.

This could be about any vaguely luxury or premium car. It certainly doesn’t highlight one of the car’s USPs (as Ogilvy’s sparkly copy did).

If a creative agency provided this to you, you’d fire them. And, quite rightly so.

Listen to the scores of AI boosters online and they’ll eagerly describe how AI can be used as a brilliant ‘hack’, not realising that the term ‘hack’ is used amongst writers as a pejorative to describe someone who writes low-quality garbage…

The algorithmic flattening of writing

Which brings me to my next point. By its very nature, large-language models are designed to be ‘average’.

I’m no artificial intelligence scientist, but, from what I’ve read, LLMs use statistical modelling to guess what the next word in a sentence should be on average.

Just as social media platforms such as Instagram have introduced a form of ‘cultural algorithmic flattening’, LLMs will do the same for the written word.

This cultural homogenisation is perhaps best exemplified by the archetype of high-street hipsterdom; the coffee shop. You can test this for yourself. Go to your local trendy coffee shop and see if it ticks the ‘Insta’ criteria:

- Large volumes of natural light from a floor-to-ceiling storefront window.

- Oversized, industrial-style wooden tables (perhaps accented with some steel scaffolding pipe).

- Skimmed concrete floor and/or walls.

- Minimalist risograph prints appended to the walls via foldback clips.

- Plentiful potted plants (ficus elastica and monstera deliciosa being particularly prevalent examples).

The chances are, your local hipster coffee shop ticks at least some (if not all) of these boxes.

This is cultural algorithmic flattening in action. From Brisbane to Birmingham, coffee shops - as mediated by the Internet - are aesthetically converging, providing an experience that is algorithmically determined by social media giants like Meta.

If you haven’t gathered so far, I don’t think this is a good thing!

And, the same is happening to the written word thanks to AI. Ask ChatGPT or CoPilot to create a short article, email or some generic copy on any topic and you’ll be provided with the same stilted syntax, weirdly assertive declarative sentences, and a smattering of contextually irrelevant superlatives and god is it generic.

If you’re any form of committed reader or writer, then you can tell when a segment of writing has been created using AI. And, it’s depressing.

Of course, aside from regressing to mediocrity and banality, the spread of AI content has broader implications in terms of the homogenisation of viewpoints. If you do want to market a product/service/venue in an unorthodox way, AI will continually try and steer you towards the average.

“No”, it seems to be saying, “your coffee shop shouldn’t resemble a Baroque palace. Instead, it should resemble all those other coffee shops typified by a (strict) adherence to the Mid Century minimalist aesthetic.

Furthermore - and a tip of the hat to my colleague John Warner for this insight - if AI copy becomes the norm amongst the largest brands, it’s likely to directly impact how people write - we’re creatures that naturally imitate - so new writers may end up writing in that horrible AI tone-of-voice.

You get my point (hopefully)...

Read this next - if you’re interested in this concept of algorithmic flattening then read Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture by Kyle Chayka which is arguably the best exploration of this phenomenon.

The lessons of literature

If there’s anyone who should care about the value of the written word, it’s writers. And, there are plenty of examples of writers who have warned of the risks of outsourcing our writing (and by implication our thinking) to others (especially AI).

Perhaps the most prescient (and scary) example is Frank Herbert. In the first of the Dune series of novels, Herbert explains the origins behind the Butlerian Jihad - a universe-wide crusade that eventually saw the destruction and prohibition of ‘thinking machines’.

He succinctly summaries the impetus of this anti-tech jihad:

“Once men turned their thinking over to machines in the hope that this would set them free… but that only permitted other men with machines to enslave them”.

Forgive me for flirting ever-so-slightly with the conspiratorial, but those pushing AI the hardest are those currently in positions of immense wealth and power.

I’ll say no more on that, but do you really want to outsource your thinking?!

In my darker moments, I tend to think that people will happily outsource their thinking (and perhaps even freedom) if it buys them ever greater degrees of comfort.

But, think of the long-term effects of outsourcing your writing (and thus thinking). There’s actually a historic example of this that we can witness today.

Around two to three decades ago, we outsourced our collective numeracy to calculators. Although evidence is mixed, a number of studies have suggested that a ‘non-trivial’ number of people will uncritically accept the outputs of calculators.

Will the same happen with AI-generated words? My answer is almost certainly.

To take another example of how technology easily breeds uncritical acceptance, consider the multiple cases during the mid to late noughties of individuals who willingly drove their cars into rivers or ponds. They trusted the output of a satnav (remember those?!) over the evidence of their own senses.

The widespread use of AI is almost certainly going to lead to a significant increase in ‘memetic falsehoods’. Aptly summarised as, “if ChatGPT said it, it must be true”. This is a phenomenon that was already a problem with fake news on platforms like Facebook. AI models like ChatGPT are likely to supercharge this issue even more.

Solow’s Paradox

Okay. I’ve hopefully made the limitations of AI-produced content fairly clear by now.

However, I can see an all-too-familiar objection cresting the rhetorical horizon.

The objection?

That, even despite its flaws, AI content is fast, free, and fancy.

It can, admittedly, churn out thousands of words in tens of seconds.

However, many of the proposers of this argument have overlooked (or never even heard of) Solow’s Paradox.

Attributed to the American economist Robert Solow, Solow’s Paradox (also known as the ‘Productivity Paradox’) posits that ‘despite the introduction of information technology (IT) into the workplace from the 1980s, productivity has failed to increase (and in some instances has decreased!)’.

Solow himself pithily summarised his theory with the observation that, “you can see the impact of the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics”.

A quick dive into the numbers demonstrates the truth of this paradox. The computing capacity of the U.S. increased a hundredfold in the 1970s and 1980s, yet labour productivity growth slowed from over 3% in the 1960s to roughly 1% in the 1980s.

I believe that Solow’s Paradox applies to AI and content.

Think of it like this:

- You task an LLM with creating a blog via a prompt.

- The LLM outputs a few hundred words of content.

- It’s mediocre and generic.

- You try further prompts (the clock continues to tick whilst you do this).

- The LLM outputs some more text which is a little more honed.

- You try even more prompts (tick tock, tick tock).

- By the time you get to the fourth or fifth prompt, the AI has forgotten (or massively deviated from your initial prompt) and thus you end up untethered from your initial point. More work ensues.

- You end up with a blog that’s a little less generic than the initial effort.

- Now you’ve got to read it from start to finish (more time).

- Where did that fact come from? Is it a hallucination? You dive into Google to try and find the source of the fact. The clock continues to tick…

- The LLM has referred to a concept/theory/formula. Is it contextually correct? You need to check this.

- The LLM has ‘helpfully’ littered the text with needless superlatives. You spend time removing these or finding more suitable synonyms.

- The LLM has used American grammatical rules. Great. You spend time editing these out.

- You end up rewriting great chunks of the text, removing entire paragraphs, running several sections through plagiarism checkers and more.

It’s my contention that, at the end of this rigmarole, you’ll end up with a piece of content that’s okay (but, not great) and you’ll have likely spent as much time (if not more) as if you’d just sat down and written the damn thing from scratch.

Put it this way; if you actually care about what you’re writing, there’s little to no time to be saved from using an AI writing tool.

Or, to put it another way; AI writing tools are only worthwhile if you’re not particularly bothered about the end result.

Which brings me to my next point.

AI and civilisational collapse

The rise of AI writing tools has provided a shortcut for the lazy. Can’t be bothered to think of an email? There’s an AI for that. Can’t be arsed reviewing that academic paper? Just get ChatGPT to do it.

This isn't merely conjecture, either.

We’re already seeing scientific journals publishing papers containing AI-generated text. Peer reviewers (who should know better) are using ChatGPT to do their jobs for them. And, supposed repositories of knowledge like Google Books are indexing AI-generated rubbish.

Universities and colleges are being faced with the ‘death of the essay’.

If this persists (and it almost certainly will), this will have serious consequences.

If you are able to use AI to write your assignments for you, complete your academic paper, or write a peer review paper, then we’ll see a ‘hollowing out’ of knowledge. We face the very real prospect of people graduating with degrees with little to no knowledge of the subject matter they majored in.

Surely, it doesn’t take a genius to see the long-term consequences of such a trend?!

As I keep obsessively repeating throughout this essay; outsource your writing and you’re outsourcing your thinking.

The Gutenberg Parenthesis

Ever since the term ‘Gutenberg Parenthesis’ was coined by Danish academic Lars Ole Sauerberg, it has been an interesting idea, but one that seemed unlikely to come to fruition.

If you’re not familiar with the Gutenberg Parenthesis, it’s the idea that the use of the written word will be a mere ‘blip’ within the broader history of mankind.

The invention of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press in the mid-15th century ushered in an era in which the written word became the dominant form of information storage and propagation.

Sauerberg theorised that the rise of digital technology (especially TV, films and the Internet) would lead to the death of the written word. (As an aside, the modern movie does come close to representing Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk).

It didn’t quite pan out like that.

But, with the rise of AI-generated content, could we see a drastic change? In an era when nobody bothers to write anything, when you don’t know if a book was written by a real person or not, will the written word wither and die on the vine?

I don’t know, but there’s a possibility that AI could represent the closing parenthesis of the Gutenberg epoch.

To write, is to live

I appreciate that this essay has struck a largely lugubrious tone throughout; so, I’d like to end on a more positive note.

The tech bros of Silicon Valley seem to dream of a future in which the act of writing is hollowed out. They seem to want the act of writing to be rendered down into the process of inputting a few prompts and uncritically accepting the output of their LLMs.

However, despite their assertions to the contrary, this is a bleak, dystopian future.

Writing, like many other creative acts, is a means by which individuals can attain self-actualisation and fulfilment. The process of writing can be the reward.

Remove the process of actually putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard and you reduce writing to a soulless, mechanistic act.

It’s for exactly this reason that I don’t think the written word (that is, the true, human written word) will die. There will always be people - like myself - who refuse to outsource their thinking to machines. People who want to be 100% responsible for the words they put out into the world. Who actually appreciate writing as an art and craft that shouldn’t be automated and homogenised.

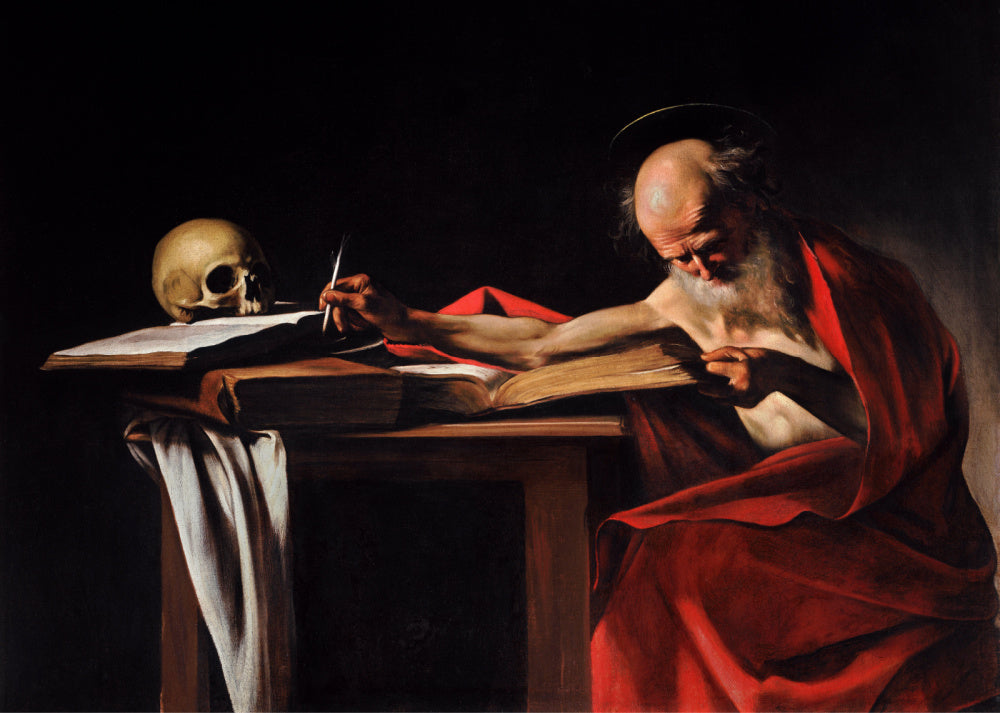

I’ll leave you with a quote from Nietzsche’s Human, All Too Human:

“Joy in old age. The thinker or artist whose better self has fled into his works feels an almost malicious joy when he sees his body and spirit slowly broken into and destroyed by time; it is as if he were in a corner, watching a thief at work on his safe, all the while knowing that it is empty and that all his treasures have been rescued”.